Potrzebie

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Four Color Fear

It seems unfortunate to me that cartoonist Howard Nostrand (1929-1984) was not a contributor to the early Mad comic book. He would have been a comfortable fit, more so than John Severin.

Below is Nostrand's strange, surreal "What's Happening at... 8:30 P.M." from Witches Tales #25 (June 1954). This has just been reprinted in Greg Sadowski and John Benson's noirish, nightmarish Four Color Fear, an anthology of pre-Code 1950s terror tales, coincidentally shipping during Banned Books Week (September 25 to October 2).

When I interviewed Nostrand in 1968, I carried along a copy of Witches Tales #25. I asked him about Harvey Comics, Bob Powell and this story: "Harvey had a sort of chicken attitude about horror stuff. Like it should be horrible but not too horrible. Granted, they get a little ghastly every once in a while, but I suppose they wanted to keep it in fairly good taste. When you look at '8:30 P.M', there's nothing particularly horrible about it. It's a little germ wandering around. And the fact that the germ gets killed, nobody's going to lie awake at night thinking about it."

He also spoke about the Eisner-like title billboard in the splash and achieving atmospherics on the first page: "Powell was a great fan of Hitchcock's, same way that Eisner was. You look at an old Hitchcock movie... the first thing you do is set the scene. This is what I tried to do in a lot of these things. You set a mood for the whole thing. With about the first three shots, you set the mood, and then you go from there... Eisner used to get his titles in the opening panel there. The treatment is strictly Eisner. But then again, the background and all that is EC." Nostrand also commented on the unusual coloring: "It's supposed to be on the inside of a body, and so everything is kind of reddish. The only thing that isn't red is this foreign body."

This analogy between the interior of a city and a human body, linked only by redness, is what makes this story remarkable, actually more imaginative than such movies as Fantastic Voyage (1966) and Innerspace (1987). As I wrote years ago, it has more in common with Samuel Beckett's journey into self-perception, Film (1965), shot in lower Manhattan with a dying Buster Keaton. You can see Film here.

Strange synchronicity when I wrote about this story in the early 1980s for The Comics Journal: I wanted to compare it with Film and wished I had a copy of the obscure book about the Beckett movie published years earlier by Evergreen Books. I shlepped up the hill toward the usual Saturday afternoon yard sale. There was a table with only about 20 books. One of them was the very book I needed. Stunned, I gave someone 35 cents for the book, walked back down the hill and continued typing.

I feel lucky Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s (Fantagraphics, distributed by W.W. Norton) made it here. One side of the W.W. Norton cardboard mailer was ripped open with the book poking out. The mailer was too big, causing the unwrapped book to slide around inside. Someone at the Post Office put it in a plastic bag, and it was delivered hanging on the mailbox where it stayed overnight. You would think a company like W.W. Norton would have figured out how to package books for mailing by now.

Greg Sadowski and John Benson did a superb job on this collection of early 1950s horror stories, including Wood's "The Thing from the Sea" from Eerie #2 (August-September 1951) and Joe Kubert's beautifully drawn "Cat's Death" from Strange Terrors #7 (March 1963). Also included: Fred Kida, Everett Raymond Kinstler, Basil Wolverton, Al Williamson, Frank Frazetta, George Evans, Sid Check, Jack Cole, Bob Powell and others. There's a spectacular section of 32 front covers, full bleed on slick paper, including covers by Wood, Frazetta, Lee Elias and Norm Saunders.

In addition to Greg's attractive design throughout, he delivers meticulous, pixel-perfect restorations, quite evident to me when I compared the reprint of "What's Happening at... 8:30 P.M." with the original comic book. In the pages above, scanned directly from the book, one can see Greg's patience and precision in creating flawless restorations. It can also be quite time consuming, as I recall from 1988-89 when I did restoration work on ten volumes of NBM's Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy book series.

There are 25 pages of fascinating, informative notes by both Greg and John. I love that line "Comic Media... featured a rising sales chart as its logo". The book has an interactive aspect as one turns back and forth from stories and covers to the notes. The "Cover Section Key" shows the influence of web design, as each note about a cover is accompanied by a full-color thumbnail of the cover.

In an attempt to nail down which issues are "true horror comics", John Benson lists 1,371 pre-Code issues representing 110 titles from 30 companies. He also contributes a full article analyzing the work of scripter-editor Ruth Roche, noting, "Many 1950s horror comics featured violence, gore and menace for their own sake, but in Roche's world they were often only suggested, for they were merely manifestations of her real subject: the unbridled evil and chaos that was always lurking just beneath the surface, waiting to escape into the world. The innocent died with the guilty in her stories, and sometimes the particular personification of evil would still be at large at the story's end. A chilling variation on the theme of hidden chaos is the discovery that a loved one or trusted figure is actually 'the other' (a theme effectively used in the movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers a few years later). 'Evil Intruder' tellingly develops this theme and is one of the more horrifying stories in the whole genre." The slobbering love-starved creature in this outré story (from Journey into Fear #12) is totally unlike anything one might see in fantasy films or TV.

I don't like to read an article reversed into black, but even so, the inside front cover, title pages, contents page and intro, unified by the black background surrounding colorful typographic devices, all demonstrate Greg's skill as an inventive designer.

The only real flaw is the Adam Grano cover design. I always disliked the idea of enlarging panels to show halftone dots. Maybe this was clever 40 years ago, but now it's just annoying. Greg could have easily designed a much better cover, possibly by combining his logo-like title page creation with the Frank Frazetta/Sid Check cover of Beware #10 (July 1954), showing the undead about to toss a gravity-defying girl into an open grave.

This book is like time-traveling, a document of an era. Some of these stories and covers I barely recall, some are familiar and others are new to me. This will stand as an important reference work that should be shelved alongside David Hajdu's The Ten-Cent Plague. Where Hajdu detailed the behind-the-scenes political machinations and wild witchhunts of the 1950s anti-comics crusade, Four Color Fear shows what was actually available on newsstands at the time.

One minor error: The 1931-38 horror-fantasy radio series which inspired Gaines was The Witch's Tale, not The Old Witch's Tale. The host-narrator of the series was not the Old Witch, but Old Nancy, the Witch of Salem. Miriam Wolfe, who died in 2000, was 13 years old when she began portraying the cackling Old Nancy. The program's creator, Alonzo Deen Cole, provided the meows of Old Nancy's coal black cat Satan. To hear The Witch's Tale, go here.

For PDF preview of Four Color Fear with four complete stories, go here.

Below is Nostrand's strange, surreal "What's Happening at... 8:30 P.M." from Witches Tales #25 (June 1954). This has just been reprinted in Greg Sadowski and John Benson's noirish, nightmarish Four Color Fear, an anthology of pre-Code 1950s terror tales, coincidentally shipping during Banned Books Week (September 25 to October 2).

When I interviewed Nostrand in 1968, I carried along a copy of Witches Tales #25. I asked him about Harvey Comics, Bob Powell and this story: "Harvey had a sort of chicken attitude about horror stuff. Like it should be horrible but not too horrible. Granted, they get a little ghastly every once in a while, but I suppose they wanted to keep it in fairly good taste. When you look at '8:30 P.M', there's nothing particularly horrible about it. It's a little germ wandering around. And the fact that the germ gets killed, nobody's going to lie awake at night thinking about it."

He also spoke about the Eisner-like title billboard in the splash and achieving atmospherics on the first page: "Powell was a great fan of Hitchcock's, same way that Eisner was. You look at an old Hitchcock movie... the first thing you do is set the scene. This is what I tried to do in a lot of these things. You set a mood for the whole thing. With about the first three shots, you set the mood, and then you go from there... Eisner used to get his titles in the opening panel there. The treatment is strictly Eisner. But then again, the background and all that is EC." Nostrand also commented on the unusual coloring: "It's supposed to be on the inside of a body, and so everything is kind of reddish. The only thing that isn't red is this foreign body."

This analogy between the interior of a city and a human body, linked only by redness, is what makes this story remarkable, actually more imaginative than such movies as Fantastic Voyage (1966) and Innerspace (1987). As I wrote years ago, it has more in common with Samuel Beckett's journey into self-perception, Film (1965), shot in lower Manhattan with a dying Buster Keaton. You can see Film here.

Strange synchronicity when I wrote about this story in the early 1980s for The Comics Journal: I wanted to compare it with Film and wished I had a copy of the obscure book about the Beckett movie published years earlier by Evergreen Books. I shlepped up the hill toward the usual Saturday afternoon yard sale. There was a table with only about 20 books. One of them was the very book I needed. Stunned, I gave someone 35 cents for the book, walked back down the hill and continued typing.

The stories in Four Color Fear are public domain, but the

specific restored images and design are ©2010 Fantagraphics Books.

specific restored images and design are ©2010 Fantagraphics Books.

I feel lucky Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s (Fantagraphics, distributed by W.W. Norton) made it here. One side of the W.W. Norton cardboard mailer was ripped open with the book poking out. The mailer was too big, causing the unwrapped book to slide around inside. Someone at the Post Office put it in a plastic bag, and it was delivered hanging on the mailbox where it stayed overnight. You would think a company like W.W. Norton would have figured out how to package books for mailing by now.

Greg Sadowski and John Benson did a superb job on this collection of early 1950s horror stories, including Wood's "The Thing from the Sea" from Eerie #2 (August-September 1951) and Joe Kubert's beautifully drawn "Cat's Death" from Strange Terrors #7 (March 1963). Also included: Fred Kida, Everett Raymond Kinstler, Basil Wolverton, Al Williamson, Frank Frazetta, George Evans, Sid Check, Jack Cole, Bob Powell and others. There's a spectacular section of 32 front covers, full bleed on slick paper, including covers by Wood, Frazetta, Lee Elias and Norm Saunders.

In addition to Greg's attractive design throughout, he delivers meticulous, pixel-perfect restorations, quite evident to me when I compared the reprint of "What's Happening at... 8:30 P.M." with the original comic book. In the pages above, scanned directly from the book, one can see Greg's patience and precision in creating flawless restorations. It can also be quite time consuming, as I recall from 1988-89 when I did restoration work on ten volumes of NBM's Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy book series.

There are 25 pages of fascinating, informative notes by both Greg and John. I love that line "Comic Media... featured a rising sales chart as its logo". The book has an interactive aspect as one turns back and forth from stories and covers to the notes. The "Cover Section Key" shows the influence of web design, as each note about a cover is accompanied by a full-color thumbnail of the cover.

In an attempt to nail down which issues are "true horror comics", John Benson lists 1,371 pre-Code issues representing 110 titles from 30 companies. He also contributes a full article analyzing the work of scripter-editor Ruth Roche, noting, "Many 1950s horror comics featured violence, gore and menace for their own sake, but in Roche's world they were often only suggested, for they were merely manifestations of her real subject: the unbridled evil and chaos that was always lurking just beneath the surface, waiting to escape into the world. The innocent died with the guilty in her stories, and sometimes the particular personification of evil would still be at large at the story's end. A chilling variation on the theme of hidden chaos is the discovery that a loved one or trusted figure is actually 'the other' (a theme effectively used in the movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers a few years later). 'Evil Intruder' tellingly develops this theme and is one of the more horrifying stories in the whole genre." The slobbering love-starved creature in this outré story (from Journey into Fear #12) is totally unlike anything one might see in fantasy films or TV.

I don't like to read an article reversed into black, but even so, the inside front cover, title pages, contents page and intro, unified by the black background surrounding colorful typographic devices, all demonstrate Greg's skill as an inventive designer.

The only real flaw is the Adam Grano cover design. I always disliked the idea of enlarging panels to show halftone dots. Maybe this was clever 40 years ago, but now it's just annoying. Greg could have easily designed a much better cover, possibly by combining his logo-like title page creation with the Frank Frazetta/Sid Check cover of Beware #10 (July 1954), showing the undead about to toss a gravity-defying girl into an open grave.

This book is like time-traveling, a document of an era. Some of these stories and covers I barely recall, some are familiar and others are new to me. This will stand as an important reference work that should be shelved alongside David Hajdu's The Ten-Cent Plague. Where Hajdu detailed the behind-the-scenes political machinations and wild witchhunts of the 1950s anti-comics crusade, Four Color Fear shows what was actually available on newsstands at the time.

One minor error: The 1931-38 horror-fantasy radio series which inspired Gaines was The Witch's Tale, not The Old Witch's Tale. The host-narrator of the series was not the Old Witch, but Old Nancy, the Witch of Salem. Miriam Wolfe, who died in 2000, was 13 years old when she began portraying the cackling Old Nancy. The program's creator, Alonzo Deen Cole, provided the meows of Old Nancy's coal black cat Satan. To hear The Witch's Tale, go here.

For PDF preview of Four Color Fear with four complete stories, go here.

Labels: beckett, benson, eisner, gaines, hajdu, kurtzman, mad, nostrand, sadowski, severin, wolfe

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Wood Chips 14: A visual book review of Jules Feiffer's Backing into Forward

Reviewing this book for Publishers Weekly, I wrote:

As a kid (he was born in 1929), drawing comic strip characters on the sidewalk was a way to avoid Bronx bullies: “I was never not afraid.” Serving an apprenticeship with cartoonist Will Eisner, he felt he was a fraud (“My line was soft where it should be hard, my figures amoebic when they should be overpowering”), so he instead graduated to ghostwriting Eisner's The Spirit. His account of hitchhiking cross-country invades Kerouac territory, while his ink-stained memories of the comics industry rival Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize–winning fictional portrait. Two years in the military gave Feiffer fodder for the trenchant Munro (about a child who is drafted). Such satirical social and political commentary became the turning point in his lust for fame, which finally happened, after many rejections, when acclaim for his anxiety-ridden Village Voice strips served as a springboard into other projects. Writing with wit, angst, honesty, and self-insights, Feiffer shares a vast and complex interior emotional landscape. Intimate and entertaining, his autobiography is a revelatory evocation of fear, ambition, dread, failure, rage, and, eventually, success.

Wood on Feiffer: Jules Feiffer's Outer Space Spirit script and rough as drawn and inked by Wally Wood.

Wood on Feiffer: Jules Feiffer's Outer Space Spirit script and rough as drawn and inked by Wally Wood.

Feiffer 's friend, Ed McLean, who became a legend in direct marketing copywriting, died August 13, 2005. In 1947, Feiffer asked for a raise, and Eisner instead gave him his own page in the Spirit section. Feiffer used it to create his first professional comic strip, Clifford. Feiffer probes his innermost thoughts, anxieties and memories in this compelling autobiography, and he devotes five pages to his struggle with Clifford, recalling, "It turned out to be more natural for me to write an episode of The Spirit than to write and draw my own comic strip... Now, even though I had preceded both Schulz and Watterson with my kids' strip, I was still too young and callow (and cautious) to make my point or make my mark... Without Eisner's guidelines, I was on my own, and not up to it." Below is a Wood story from the period Feiffer described. "Man from the Grave!" in The Haunt of Fear 4 (November-December 1950) was one of five horror tales Wood did for The Haunt of Fear. Wood did a total of nine horror stories and several horror covers for EC during 1950-51.

Below is a Wood story from the period Feiffer described. "Man from the Grave!" in The Haunt of Fear 4 (November-December 1950) was one of five horror tales Wood did for The Haunt of Fear. Wood did a total of nine horror stories and several horror covers for EC during 1950-51.

Feiffer at the Strand Bookstore (May 15, 2008)

In the early 1950s, after rejections of his books by numerous publishers (as he describes in Backing into Forward and the Strand Bookstore clip), Feiffer finally scored when his Sick, Sick, Sick comic strip began in the October 24, 1956 issue of the Village Voice. To launch his Voice strip, he wrote about his own stomach spasms and drew it with a UPA style, as he explained: "The drawing style, I decided, should be direct, cartoony, animated, akin to what I so admired coming out of the UPA studios, Gerald McBoing-Boing and The Nearsighted Mr. Magoo. The more painful the subject, the funnier it should look. So my chronic stomachaches took center stage for my first Village Voice cartoon in October 1956, turning a psychosomatic problem into a metaphor. For what? Who cared? It just seemed funny."

Jules Feiffer

Reviewing this book for Publishers Weekly, I wrote:

As a kid (he was born in 1929), drawing comic strip characters on the sidewalk was a way to avoid Bronx bullies: “I was never not afraid.” Serving an apprenticeship with cartoonist Will Eisner, he felt he was a fraud (“My line was soft where it should be hard, my figures amoebic when they should be overpowering”), so he instead graduated to ghostwriting Eisner's The Spirit. His account of hitchhiking cross-country invades Kerouac territory, while his ink-stained memories of the comics industry rival Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize–winning fictional portrait. Two years in the military gave Feiffer fodder for the trenchant Munro (about a child who is drafted). Such satirical social and political commentary became the turning point in his lust for fame, which finally happened, after many rejections, when acclaim for his anxiety-ridden Village Voice strips served as a springboard into other projects. Writing with wit, angst, honesty, and self-insights, Feiffer shares a vast and complex interior emotional landscape. Intimate and entertaining, his autobiography is a revelatory evocation of fear, ambition, dread, failure, rage, and, eventually, success.

Wood on Feiffer: Jules Feiffer's Outer Space Spirit script and rough as drawn and inked by Wally Wood.

Wood on Feiffer: Jules Feiffer's Outer Space Spirit script and rough as drawn and inked by Wally Wood.In Jules Feiffer's memoir, Backing into Forward (due in March from Doubleday), he describes the Wood studio of the early 1950s (located where Lincoln Center is today). Feiffer was 17 when he began at Will Eisner's studio. Working alongside letterer Abe Kanegson, he graduated from ruling lines and erasing to coloring, and he was 19 when he started scripting The Spirit for Eisner. After meeting Wood at Eisner's shop, he began visiting the Wood studio where he became friends with Ed McLean, as he recalled:

Excerpt ©2010 by Jules Feiffer

Wally Wood, maybe a year older than I, was brought back to our office by Will, who was impressed by his samples (no threat to me, he drew backgrounds). Woody was from the Midwest. Enviably handsome, he had a squinting, tousled, mischievous charm. His squint let you know that he knew a lot more than he was saying, which was good, because he was at a loss for conversation. He seemed to be wary of speech, his prolonged silences made him formidable. While Abe and I wisecracked like smart-ass New York Jews, Woody, in no way Jewish, made sly elliptical comments that were possibly profound had we only understood what he was saying.

He shared studio space in a rundown walk-up in a Puerto Rican neighborhood in the Sixties on the Upper West Side (now Lincoln Center) with two other cartoonists and a couple of writers for comic books, already in training, with the help of beer, Chianti, and cheap rye, to make it to the top as the next generation of comic strip roustabouts. In the mid- and late forties, the first step to success for ambitious young men in the low arts was to make a mark in comic books as illustrator or writer and break into syndication with your own daily strip before you were 30.

Cartoonists like Woody saw this as the end of the road, although some others who had the facility dreamed of moving further upscale to magazine illustration. That market was still flourishing, with the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Esquire, Cosmopolitan, Liberty. A writer’s ambition, beyond comics, leaned toward breaking into the sci fi market… Woody introduced me to his studio mate, a lettering man named Ed McLean, who within minutes let me know that comics were not his end game, that his plan was to write the Great American Novel… Ed intended to impress me, and he did immediately. We met on my first visit to Woody’s studio, a long room that deepened and darkened as your eyes failed to get used to it. Artists and writers sat like galley slaves at desks and drawing tables jammed close enough together to constitute a single piece of furniture, an intimidating world of cluttered comic pages and pounding typewriters, dingy and roach-rich. The no-frills ferocity of the place was intoxicating.

©Jules Feiffer

Below is a Wood story from the period Feiffer described. "Man from the Grave!" in The Haunt of Fear 4 (November-December 1950) was one of five horror tales Wood did for The Haunt of Fear. Wood did a total of nine horror stories and several horror covers for EC during 1950-51.

Below is a Wood story from the period Feiffer described. "Man from the Grave!" in The Haunt of Fear 4 (November-December 1950) was one of five horror tales Wood did for The Haunt of Fear. Wood did a total of nine horror stories and several horror covers for EC during 1950-51.©WMG

Feiffer at the Strand Bookstore (May 15, 2008)

In the early 1950s, after rejections of his books by numerous publishers (as he describes in Backing into Forward and the Strand Bookstore clip), Feiffer finally scored when his Sick, Sick, Sick comic strip began in the October 24, 1956 issue of the Village Voice. To launch his Voice strip, he wrote about his own stomach spasms and drew it with a UPA style, as he explained: "The drawing style, I decided, should be direct, cartoony, animated, akin to what I so admired coming out of the UPA studios, Gerald McBoing-Boing and The Nearsighted Mr. Magoo. The more painful the subject, the funnier it should look. So my chronic stomachaches took center stage for my first Village Voice cartoon in October 1956, turning a psychosomatic problem into a metaphor. For what? Who cared? It just seemed funny."

©Jules Feiffer

Labels: andelman, clifford, crypt, eisner, feiffer, haunt, mclean, pw, wood, wood chips

Friday, December 19, 2008

Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist (2007)

.

Trailer: Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist from Montilla Pictures

Click here to continue reading interview.

Jon B. Cooke, Will Eisner and Andrew D. Cooke in 2004. Dave Gibbons' tribute to Eisner on the cover of Jon B. Cooke's Comic Book Artist 6. For all six issues, go here.

Will Eisner's The Spirit ventured into science fiction in the early 1950s. Wood, working from layouts by Jules Feiffer, drew eight weeks worth of Spirit strips which ran from July 1952 to October 5, 1952. "Mission... the Moon" was published August 3.

Trailer: Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist from Montilla Pictures

Andrew Cooke: Okay. Well, my brother Jon is an editor and creator of Comic Book Artist magazine, and I grew up reading comic books. I would say the two obsessions I had growing up were comics and movies. Jon and I collected all sorts of comic books, but we weren’t really aware of Will’s work until the Warren reprints came out. Once the Warren reprints came out, it just really hit us like, who was this guy? It was amazing work. Jon has our collection of our comics, but the things that I still retained, that I kept with me, were pristine, mint versions of those Warren issues. I loved them.

After high school and college, I decided to go into the movie business, and I sort of went away from comic books, and Jon, obviously, stayed with comic books. Several years ago Jon called me. We have done several projects together and had talked about making a movie together, and he called me and said, “What about a documentary about Will Eisner?” I thought, Wow, what a great idea. So we talked about it, and we talked to Will about it, and Will said yes, and so that sort of started the process. It was as simple as that. Jon wanted to honor Will in a documentary, and I thought that that was such a great idea. I would have to say that we had hoped we would have finished the documentary while he was still with us, but the progress, it just has taken us so long to do it.

Click here to continue reading interview.

Jon B. Cooke, Will Eisner and Andrew D. Cooke in 2004. Dave Gibbons' tribute to Eisner on the cover of Jon B. Cooke's Comic Book Artist 6. For all six issues, go here.

©2008 Wood and Eisner Estates

Will Eisner's The Spirit ventured into science fiction in the early 1950s. Wood, working from layouts by Jules Feiffer, drew eight weeks worth of Spirit strips which ran from July 1952 to October 5, 1952. "Mission... the Moon" was published August 3.

Labels: andelman, cooke, eisner, feiffer, gibbons, outer space, the spirit, warren

Sunday, December 25, 2005

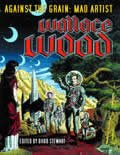

Wallace Wood: Against the Grain, part two

Saving newspaper strips to study his favorites, the young Wally Wood was attracted to the adventurous settings of Flash Gordon, Captain Easy, and Terry and the Pirates; under his mother’s supervision he made an easy leap from comics to reading books. His reading skills, developed outside of the classroom, enabled him to go directly from the third to the fifth grade. “Wally was really a bookworm,” said Glenn. “My mother got him interested in reading at a very early age. Even before he started grade school he was reading; my mother was tutoring him. When he was in the early grades, he was reading well beyond his level and on his own. He was reading into ancient history. He would dive into this stuff and devour a book in short order. He had a tremendous appetite for reading.”

Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant began in 1937, the year Woody was ten years old, and Foster moved to the forefront of his favorites, along with Caniff, Raymond and Roy Crane. Wood’s friend and associate Bill Pearson notes, “The major influence, in my view, was Roy Crane. Both Woody and I considered Crane the master of masters. At different times he cited different artists as major influences. He saw Foster as a master illustrator and Crane as a master storyteller.” When Wood was interviewed by Rick Stoner in 1978, he remarked, “The main one is Foster, but I’ve been influenced by lots of people — Raymond, Caniff, Crane, Eisner, Basil Wolverton and Walt Kelly.”

An illustrator named Wally Wood produced work during the Thirties for the Saalfield Publishing Company in Akron, Ohio; his signature appears on the front covers of two Saalfield coloring books, The Three Little Pigs (1937) and Puss in Boots (1937), but Woody was unaware of the existence of this other Wally Wood until years later, as revealed by a comment he made to Bill Pearson during the Sixties. Going through Wood’s files, Pearson was surprised to find the two coloring books, examined them and asked, “Woody, what’s this?” Wood glanced at the two books and replied, “A fan sent them to me. I don’t know anything about them.”

The same year that Woody fell under the spell of Prince Valiant, his family began the series of moves that took them across the Great Lakes region, first putting down stakes in the lumber center of Park Falls, Wisconsin, on the Flambeau River. “The logging operations started when we moved from Menahga to Park Falls, Wisconsin, about 1937,” said Glenn. “Then from 1937 through the time I graduated from Wakefield High School in 1943, we were moving through upper Wisconsin and upper Michigan. We were in Park Falls for a matter of months, and then my dad took on a more extended logging operation down in Rib Lake, Wisconsin, further south. I remember going to school with Wally in Rib Lake; we were there for about a year. In 1938, 1939, and 1940, we were in Iron Belt, Wisconsin. From there the family moved to Montreal, Wisconsin, a mining town just ten miles away. Wally and I went to the Hurley, Wisconsin, high school for a year together; in Hurley High School at that time I was a junior. My senior year was in Wakefield, Michigan, which was about 25 miles from the border in another mining town. All this time my dad was in different woods, working jobs, and we didn’t see much of him. He would come home maybe every two months or so. Mother would be head of the house. These logging camps would be 30 or 40 miles from wherever we were, and he would come in maybe in six weeks, maybe eight weeks. There were long periods when we wouldn’t see dad at all.”

Woody was 12 years old when the top names in country and western music found a national audience over the NBC radio network. The Grand Ole Opry began in 1925 over WSM in Nashville, eventually expanding to a five-hour long Saturday night broadcast. NBC, in October 1939, started its successful long-running series of a half-hour segment of the show, sponsored by Prince Albert tobacco. Throughout the Forties Wood could tune in such Opry stars as Red Foley, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, “Tennessee Ploughboy” Eddy Arnold, Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe.

Many of the drawings Wood produced during the Thirties were penciled on a coarse, rough paper, but World War II and the V-Mail Service resulted in a free supply of smooth V-Mail paper, perfect for drawing. V-Mail was used to reduce the weight of overseas mail deliveries, as explained in the V-Mail instructions: “When addressed to points where micro-film equipment is operated, a miniature photographic negative of the message will be made and sent by the most expeditious transportation available for reproduction and delivery. The original message will be destroyed after the reproduction has been delivered.” The “original message” was written on the blank side of a piece of V-Mail paper 5 5/8" wide by 9 1/8" deep that folded into an envelope. The other side featured the instructions and envelope area printed in red. With the V-Mail’s clean, white surface to draw on, Wood turned out a pile of drawings. By the time he was 15 he also managed to acquire the Duoshade paper and developing fluids marketed by Cleveland’s CrafTint Manufacturing Company; later available from Cleveland's Ohio Graphic Arts Systems (a company which changed its name to Grafix in 1990). The CrafTint paper enabled Wood to begin simulating the tonal and shading effects he had seen in Roy Crane’s work.

But these early efforts did not impress his teachers, judging by Wood’s 1980 recollection: “I always got bad marks in art. I always had the attitude toward art teachers that if they were such hotshots, why were they teaching art in a jerkwater high school? I guess it showed. Always got a ‘C’ in art.” As he continued on his path of self-study, he did not ignore the usual high school social activities. In 1942, when he was a high school sophomore, he was one of the organizers of the school’s sophomore dance party, as indicated by the line “Buy your tickets from: Wood Holcers Zell Jordan” on the jazzy and surreal poster he drew and colored to promote the event. The poster shows a jazzman riffing on “She’ll Be Comin' ’Round the Mountain,” a tune heard widely during the Thirties as recorded by the Paul Tremaine dance band (Columbia 2130-D).

On weekends, in the darkness of smalltown movie theaters, he observed the manipulation of lighting for dramatic emphasis in Hollywood films and then headed home to attempt a similar handling of light and shadow in his drawings. Rounding up his friends, he employed them as actors in 8mm films he made with a used Keystone camera. To his friends he became known as Woody, and he grew to dislike the name Wally, a feeling he expressed in the second issue (1978) of The Woodwork Gazette: “...I hate the name Wally. Ever since I was a kid it’s been ‘Woody’ — and now I have two nephews who are also Woody to their friends. And even my mother was Woody on one job she had.”

He walked past newsstands racked with colorful displays of pulp magazines, and the Bug-Eyed Monsters of Planet Stories appealed to his youthful imagination. In A Pictorial History of Science Fiction David Kyle wrote, “It was Planet Stories...which made the BEM its house pet, usually with a helpless, lightly clothed damsel in the foreground and a virile, heavily clothed, gun-slinging hero in the background,” a caption description of A. Leydenfrost’s painting for the Spring 1942 Planet Stories cover, reprinted by Kyle. In an incomplete comics page roughed by Wood in the early Forties, he swiped the head and shoulders of Leydenfrost’s alien creature; it appears in a sequence of six captioned panels containing three unfinished drawings. (Wood was not the only artist who found this creature of interest; it was also swiped ten years later by Maurice Whitman for the front cover of Planet Comics #67.)

Also in 1942 he used his CrafTint paper for studies taken from Will Eisner’s The Spirit which he read in the Minneapolis Star-Journal. One such is a copy of the background of the entire February 22, 1942, Spirit splash page. Speculating in The Outer Space Spirit on this 1942 Wood drawing, Catherine Yronwode commented, “Wood made good use of Eisner’s free weekly lessons in panel composition and lighting effects... Wood may have felt that copying the human figure was too hard, or perhaps at age 15 he had already decided to take his anatomy lessons elsewhere. The swipe is only that of the ‘stage setting’ Eisner drew, not the man standing in it.”

As the war raged on, the Wood family, uprooted a total of nine times, had left a splintered trail past the logging camps, but the trek came to an end when Glenn graduated from high school in Wakefield, Michigan. The family returned to Minnesota where the teenage Wally Wood suddenly found himself wandering the corridors of a big city high school, West High in Minneapolis, during his senior year. Glenn recalled, “I graduated and went into the Navy college program. Wally and mother joined my dad in Minneapolis. I was at Illinois Tech in Chicago from July 1943 until I graduated that program in February 1946. In the meantime, Wally went through West High, and if my memory is serving me right, that’s when he did these different jobs like dental technician and so forth. As a dental technician in Minneapolis, he made dental plates.”

Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant began in 1937, the year Woody was ten years old, and Foster moved to the forefront of his favorites, along with Caniff, Raymond and Roy Crane. Wood’s friend and associate Bill Pearson notes, “The major influence, in my view, was Roy Crane. Both Woody and I considered Crane the master of masters. At different times he cited different artists as major influences. He saw Foster as a master illustrator and Crane as a master storyteller.” When Wood was interviewed by Rick Stoner in 1978, he remarked, “The main one is Foster, but I’ve been influenced by lots of people — Raymond, Caniff, Crane, Eisner, Basil Wolverton and Walt Kelly.”

An illustrator named Wally Wood produced work during the Thirties for the Saalfield Publishing Company in Akron, Ohio; his signature appears on the front covers of two Saalfield coloring books, The Three Little Pigs (1937) and Puss in Boots (1937), but Woody was unaware of the existence of this other Wally Wood until years later, as revealed by a comment he made to Bill Pearson during the Sixties. Going through Wood’s files, Pearson was surprised to find the two coloring books, examined them and asked, “Woody, what’s this?” Wood glanced at the two books and replied, “A fan sent them to me. I don’t know anything about them.”

The same year that Woody fell under the spell of Prince Valiant, his family began the series of moves that took them across the Great Lakes region, first putting down stakes in the lumber center of Park Falls, Wisconsin, on the Flambeau River. “The logging operations started when we moved from Menahga to Park Falls, Wisconsin, about 1937,” said Glenn. “Then from 1937 through the time I graduated from Wakefield High School in 1943, we were moving through upper Wisconsin and upper Michigan. We were in Park Falls for a matter of months, and then my dad took on a more extended logging operation down in Rib Lake, Wisconsin, further south. I remember going to school with Wally in Rib Lake; we were there for about a year. In 1938, 1939, and 1940, we were in Iron Belt, Wisconsin. From there the family moved to Montreal, Wisconsin, a mining town just ten miles away. Wally and I went to the Hurley, Wisconsin, high school for a year together; in Hurley High School at that time I was a junior. My senior year was in Wakefield, Michigan, which was about 25 miles from the border in another mining town. All this time my dad was in different woods, working jobs, and we didn’t see much of him. He would come home maybe every two months or so. Mother would be head of the house. These logging camps would be 30 or 40 miles from wherever we were, and he would come in maybe in six weeks, maybe eight weeks. There were long periods when we wouldn’t see dad at all.”

Woody was 12 years old when the top names in country and western music found a national audience over the NBC radio network. The Grand Ole Opry began in 1925 over WSM in Nashville, eventually expanding to a five-hour long Saturday night broadcast. NBC, in October 1939, started its successful long-running series of a half-hour segment of the show, sponsored by Prince Albert tobacco. Throughout the Forties Wood could tune in such Opry stars as Red Foley, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, “Tennessee Ploughboy” Eddy Arnold, Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe.

Many of the drawings Wood produced during the Thirties were penciled on a coarse, rough paper, but World War II and the V-Mail Service resulted in a free supply of smooth V-Mail paper, perfect for drawing. V-Mail was used to reduce the weight of overseas mail deliveries, as explained in the V-Mail instructions: “When addressed to points where micro-film equipment is operated, a miniature photographic negative of the message will be made and sent by the most expeditious transportation available for reproduction and delivery. The original message will be destroyed after the reproduction has been delivered.” The “original message” was written on the blank side of a piece of V-Mail paper 5 5/8" wide by 9 1/8" deep that folded into an envelope. The other side featured the instructions and envelope area printed in red. With the V-Mail’s clean, white surface to draw on, Wood turned out a pile of drawings. By the time he was 15 he also managed to acquire the Duoshade paper and developing fluids marketed by Cleveland’s CrafTint Manufacturing Company; later available from Cleveland's Ohio Graphic Arts Systems (a company which changed its name to Grafix in 1990). The CrafTint paper enabled Wood to begin simulating the tonal and shading effects he had seen in Roy Crane’s work.

But these early efforts did not impress his teachers, judging by Wood’s 1980 recollection: “I always got bad marks in art. I always had the attitude toward art teachers that if they were such hotshots, why were they teaching art in a jerkwater high school? I guess it showed. Always got a ‘C’ in art.” As he continued on his path of self-study, he did not ignore the usual high school social activities. In 1942, when he was a high school sophomore, he was one of the organizers of the school’s sophomore dance party, as indicated by the line “Buy your tickets from: Wood Holcers Zell Jordan” on the jazzy and surreal poster he drew and colored to promote the event. The poster shows a jazzman riffing on “She’ll Be Comin' ’Round the Mountain,” a tune heard widely during the Thirties as recorded by the Paul Tremaine dance band (Columbia 2130-D).

On weekends, in the darkness of smalltown movie theaters, he observed the manipulation of lighting for dramatic emphasis in Hollywood films and then headed home to attempt a similar handling of light and shadow in his drawings. Rounding up his friends, he employed them as actors in 8mm films he made with a used Keystone camera. To his friends he became known as Woody, and he grew to dislike the name Wally, a feeling he expressed in the second issue (1978) of The Woodwork Gazette: “...I hate the name Wally. Ever since I was a kid it’s been ‘Woody’ — and now I have two nephews who are also Woody to their friends. And even my mother was Woody on one job she had.”

He walked past newsstands racked with colorful displays of pulp magazines, and the Bug-Eyed Monsters of Planet Stories appealed to his youthful imagination. In A Pictorial History of Science Fiction David Kyle wrote, “It was Planet Stories...which made the BEM its house pet, usually with a helpless, lightly clothed damsel in the foreground and a virile, heavily clothed, gun-slinging hero in the background,” a caption description of A. Leydenfrost’s painting for the Spring 1942 Planet Stories cover, reprinted by Kyle. In an incomplete comics page roughed by Wood in the early Forties, he swiped the head and shoulders of Leydenfrost’s alien creature; it appears in a sequence of six captioned panels containing three unfinished drawings. (Wood was not the only artist who found this creature of interest; it was also swiped ten years later by Maurice Whitman for the front cover of Planet Comics #67.)

Also in 1942 he used his CrafTint paper for studies taken from Will Eisner’s The Spirit which he read in the Minneapolis Star-Journal. One such is a copy of the background of the entire February 22, 1942, Spirit splash page. Speculating in The Outer Space Spirit on this 1942 Wood drawing, Catherine Yronwode commented, “Wood made good use of Eisner’s free weekly lessons in panel composition and lighting effects... Wood may have felt that copying the human figure was too hard, or perhaps at age 15 he had already decided to take his anatomy lessons elsewhere. The swipe is only that of the ‘stage setting’ Eisner drew, not the man standing in it.”

As the war raged on, the Wood family, uprooted a total of nine times, had left a splintered trail past the logging camps, but the trek came to an end when Glenn graduated from high school in Wakefield, Michigan. The family returned to Minnesota where the teenage Wally Wood suddenly found himself wandering the corridors of a big city high school, West High in Minneapolis, during his senior year. Glenn recalled, “I graduated and went into the Navy college program. Wally and mother joined my dad in Minneapolis. I was at Illinois Tech in Chicago from July 1943 until I graduated that program in February 1946. In the meantime, Wally went through West High, and if my memory is serving me right, that’s when he did these different jobs like dental technician and so forth. As a dental technician in Minneapolis, he made dental plates.”