Potrzebie

Sunday, January 30, 2011

First appearance of Popeye in 1929.

Above is Rick Baker's Popeye from Fire Wire's What If Cartoon Characters Were

Real? Sort of reminds of Jack Kerouac speculating about what if the Three Stooges were real in Vanity of Dulouz. Also see The Wisdom of Popeye. In his recent autobiography, Jules Feiffer explains how he wrote his Popeye screenplay based on the 1936 E.C. Segar strips in Woody Gelman's 1971 Nostalgia Press Popeye the Sailor book.

Below is from Jeff Koons' Popeye Series. For more on Koons' Popeye Series, go here.

Here is Frederic Tuten's story about Popeye, "L'Odysee", first published in Jeff Koons: Popeye Series (London: Serpentine Gallery and Koenig Books, 2009). Tuten previously did a novelization of Tintin in Tintin in the New World (2005).

To read the rest of the story, go to Literarian.

"L'Odysee" by Frederic Tuten

Then I made me way into the tottering house itself and found it all in shambles. A clothesline freighted with frilly red underwear, not mine, and three pairs of long johns, not mine, stretched across the living room. The bathroom reeked of men’s after-shave and colognes – Brute – and was littered with gum stimulators, nose-hair scissors, moustache trimmers, nail cutters and other implements and toiletries that I never use.

The bedroom. The bedroom. It stabbed me heart. Men’s boots and shoes of various sizes and shapes, quality and age were lined along the wall. But not one pair of mine in the lot.

“What! That you?” She said, pulling down the edge of her slinky black negligee.

I was charged with great emotion, seeing her spread out there in our old bed, seeing her unchanged not a jot in all the years I had been gone. Not one wrinkle, not one gray hair, not one bump or wart or blemish. She was her old skinny self with a few new appealing curves, her tongue still as sharp as her pointy elbows.

Before I could answer her, Nestor with all the juice of his youth dried out of him, limped into the room – where was his forth leg? – and gave me a steady look and a short sniff. Sniff sniff, like a sneeze that had fallen asleep; then he turned about and limped out the door as if I were not there, had never lived there, would never again live there.

“Nestor,” I cried, “It’s me.”

Not a glance me way. He may be deaf, I thought, seeing him slouch off like an old man with a missing leg, en plus. Age and loss. Twin themes I had thought would never visit me.

“Yes, it’s me come home,” I said, as she rose from the bed and wrapped about her a great green house coat which covered her from foot to neck – her head sticking out like a white bean squeezed from its pod.

“Returned home like the faithful sailor you are. Away for a thousand years and never a post card.”

“It’s a long and odd story, my dear, and one I’m eager to tell.”

“The world may be all ears but I’m not,” she said. “Your berth’s been taken, sailor, so cast off.”

She was her same wonderful biting self but with a decidedly new and attractive twist. Her once long and sharp toe nails were now trim and shaded rose. Her feet, peeking out from under the train of her robe, usually rough and dry like barnacles, were presently smooth and, dare I say, creamy. Dare I say, fetching!

Continued at Literarian. All of the above are close but no Segar. Here's the real deal:

Segar satirized cartoonists as seen in this reprint from Nemo #3 (October 1983). To read Bill Blackbeard on Segar in that issue, go Inside Jeff Overturf's Head.

After Segar died of liver disease in 1938 at age 43, his strip was continued by Tom Sims, Doc Winner, Bill Zaboly, Bud Sagendorf, Hy Eisman and Bobby London, who did the strip from 1986 until he was fired from King Features in 1992. London said, "Segar was, as far as my career, as far as making a decision to be a professional cartoonist, Segar was the seminal influence in my career."

Here's the controversial Bobby London finale with misunderstandings that ensued after Olive Oyl received a toy doll from the Home Shopping Network.

Continued at Literarian. All of the above are close but no Segar. Here's the real deal:

Popeye lifts Elzie Segar.

Segar satirized cartoonists as seen in this reprint from Nemo #3 (October 1983). To read Bill Blackbeard on Segar in that issue, go Inside Jeff Overturf's Head.

After Segar died of liver disease in 1938 at age 43, his strip was continued by Tom Sims, Doc Winner, Bill Zaboly, Bud Sagendorf, Hy Eisman and Bobby London, who did the strip from 1986 until he was fired from King Features in 1992. London said, "Segar was, as far as my career, as far as making a decision to be a professional cartoonist, Segar was the seminal influence in my career."

Here's the controversial Bobby London finale with misunderstandings that ensued after Olive Oyl received a toy doll from the Home Shopping Network.

Popeye waves goodbye.

Labels: bill blackbeard, bobby london, gelman, koons, marschall, nemo, overturf, popeye, sagendorf, segar, sims, tuten, zaboly

Monday, December 27, 2010

Robbie in the Land of Lore

.

Here is Robbie, scripted by Len Brown and illustrated by Al Williamson during the 1960s. This was an effort by Brown, Williamson and Woody Gelman to create a syndicated comic strip that would bring back the epic era of such imaginative strips as Little Nemo and Prince Valiant. Two pages were created as samples, but the days of full-page strips had already faded into the past.

The copies I have were too big for my scanner, so I had to do them in sections and then use Photoshop to jigsaw the pieces together. I then saved the final images very large so the little details Williamson drew can be easily studied. Here's how Len Brown remembers this project:

Here is Robbie, scripted by Len Brown and illustrated by Al Williamson during the 1960s. This was an effort by Brown, Williamson and Woody Gelman to create a syndicated comic strip that would bring back the epic era of such imaginative strips as Little Nemo and Prince Valiant. Two pages were created as samples, but the days of full-page strips had already faded into the past.

The copies I have were too big for my scanner, so I had to do them in sections and then use Photoshop to jigsaw the pieces together. I then saved the final images very large so the little details Williamson drew can be easily studied. Here's how Len Brown remembers this project:

Woody and I had talked about seeing if a fantasy Sunday page could be sold (with a tip of the hat to Nemo of course). We bucked the trend at the time, because full page Sunday strips were gone with the exception of an occasional paper that still ran Prince Valiant full size. In the early 1960s that was rare.

We commissioned Al to draw two Sunday pages as a sample for the syndicates. I know we submitted it to King Features and perhaps one other syndicate. I remember one of the syndicates gave nice feedback and suggested we redraw it as a daily. But I guess it was tough to get Al on it, as we didn't pay him a lot of money, and he was in demand during those days. The nature of the two Robbie pages didn't lend themselves to statting them down to a daily strip.

The artwork was lost when Woody accidentally left it outside his office one evening. The cleaning folks were used to thinking of anything outside an office was trash. I was heartbroken, Woody felt terribly about it, and I don't believe we ever told Al the sad truth. We paid him $75 a page for each of the two pages.

We commissioned Al to draw two Sunday pages as a sample for the syndicates. I know we submitted it to King Features and perhaps one other syndicate. I remember one of the syndicates gave nice feedback and suggested we redraw it as a daily. But I guess it was tough to get Al on it, as we didn't pay him a lot of money, and he was in demand during those days. The nature of the two Robbie pages didn't lend themselves to statting them down to a daily strip.

The artwork was lost when Woody accidentally left it outside his office one evening. The cleaning folks were used to thinking of anything outside an office was trash. I was heartbroken, Woody felt terribly about it, and I don't believe we ever told Al the sad truth. We paid him $75 a page for each of the two pages.

- Len Brown

© copyright 2010 by Len Brown

Labels: al williamson, gelman, len brown

Thursday, December 09, 2010

Topps #9: Wacky Packages

.

I have a memory lapse when I try to recall which Wacky Packages and Wacky Ads I devised over 35 to 40 years ago. I know one of them was the dog shaving with Rabid Shave and another was the Mustard Charge card. (See below.)

Of course, all the Wackys were much smaller than the actual products, and the main reason I did the Mustard Charge sticker was because I wanted to do a Wacky Package that could fool the eye by being the exact same size as the product being satirized.

A news story today is about the cyber attacks on Visa and MasterCard. So far as I know, no one has ever hacked into Mustard Charge.

The 1973 New York cover story is headlined Wacky Packs. I never quite understood why Topps didn't change the name to the more euphonic Wacky Packs, since that's what kids called the cards and stickers.

The usual procedure was to first go to a store, buy some products and study each until a gag came to mind. Then it was a matter of embellishing the main premise with related gags.

Working on a layout pad, one could sketch out the gag and then put the rough under another layout sheet to tighten the drawing. After inking with a Rapidograph, the rough was then colored with markers. If the color rough were accepted, editorial changes might or might not be written on it, and it would then be used as a color guide for the final art.

Back then, Topps was still in Brookyn at the Bush Terminal in Sunset Park (the setting for the new Paul Auster novel, Sunset Park). The Bush Terminal is a huge complex, used during World War II for the shipping of troop supplies to Europe. There was a plan during the 1990s to turn it into Silicon Valley East, but that never got underway.

In Topps' Product Development Department, there was a central area where secretary Faye Fleischer sat near banks of file cabinets. Creative director Woody Gelman used these to file away all rough gags, possible ideas, clippings and even various kinds of paper stocks, along with tricks, gimmicks, pop-up oddities, lenticular images and cardboard novelty items.

Gelman and writer-editor Len Brown had adjacent offices that opened into Faye's area, as did my office, which was near the offices of the imaginative Art Spiegelman, designer Rick Varesi and gagwriter Stan Hart, who had married into the company and came in only one day a week. Hart wrote the Mad movie satires and later was a two-time Emmy-winner as a scripter for The Carol Burnett Show. A door on the other side of Gelman's room led to the office of the clever cartoonist and entertaining raconteur Larry Riley, whom I described in the third installment of this series about Topps. Sometimes Jay Lynch came to New York and worked periodically in the Product Development Dept.

Each day when I entered the building, as I recall, I went past a small sign that read, "Uneeda Doll Co." The floor of my office could get quite hot, and one day I peered into the ground floor area occupied by the Uneeda company and saw fumes rising from giant boiling vats. Later I began to wonder if seepage from those fumes is why we were all going wacky in Product Development.

One day in the summer of 1968, I told Woody I was going out, left the overheated office, exited the Bush Terminal and turned on 3rd Avenue toward Bay Ridge, perspiring as I walked through the broiling Brooklyn heat to a distant supermarket. At that time of day, the place was almost deserted. I wandered the aisles, sometimes just standing and reading the copy on containers to see what might be twisted into something goofy.

I looked up and noticed the store manager at the end of an aisle, staring at me. Since my actions were not those of a usual grocery shopper, he thought I was getting ready to steal something. After making my purchases, I headed back to Topps, carrying a paper bag filled with parody potentials, including a can of frozen orange juice concentrate.

I set these up near my drawing table, locked up and took the train back to Manhattan. When I opened the office door on Monday morning, there was a surprise. With the heat rising to a bake oven temperature during the weekend, the orange juice had exploded, leaving an orangey stickiness scattered over the drawing table and the wall. It was still stuck to the wall when I left New York and moved to Boston.

Google Street View screenshot at right shows where Topps was located at 254 36th Street in Brooklyn. At left is corner of 36th Street and 3rd Avenue where Woody Gelman and Len Brown would park their cars beneath the Gowanus Expressway.

Google Street View screenshot at right shows where Topps was located at 254 36th Street in Brooklyn. At left is corner of 36th Street and 3rd Avenue where Woody Gelman and Len Brown would park their cars beneath the Gowanus Expressway.

I have a memory lapse when I try to recall which Wacky Packages and Wacky Ads I devised over 35 to 40 years ago. I know one of them was the dog shaving with Rabid Shave and another was the Mustard Charge card. (See below.)

Of course, all the Wackys were much smaller than the actual products, and the main reason I did the Mustard Charge sticker was because I wanted to do a Wacky Package that could fool the eye by being the exact same size as the product being satirized.

A news story today is about the cyber attacks on Visa and MasterCard. So far as I know, no one has ever hacked into Mustard Charge.

The 1973 New York cover story is headlined Wacky Packs. I never quite understood why Topps didn't change the name to the more euphonic Wacky Packs, since that's what kids called the cards and stickers.

The usual procedure was to first go to a store, buy some products and study each until a gag came to mind. Then it was a matter of embellishing the main premise with related gags.

Working on a layout pad, one could sketch out the gag and then put the rough under another layout sheet to tighten the drawing. After inking with a Rapidograph, the rough was then colored with markers. If the color rough were accepted, editorial changes might or might not be written on it, and it would then be used as a color guide for the final art.

Back then, Topps was still in Brookyn at the Bush Terminal in Sunset Park (the setting for the new Paul Auster novel, Sunset Park). The Bush Terminal is a huge complex, used during World War II for the shipping of troop supplies to Europe. There was a plan during the 1990s to turn it into Silicon Valley East, but that never got underway.

In Topps' Product Development Department, there was a central area where secretary Faye Fleischer sat near banks of file cabinets. Creative director Woody Gelman used these to file away all rough gags, possible ideas, clippings and even various kinds of paper stocks, along with tricks, gimmicks, pop-up oddities, lenticular images and cardboard novelty items.

Gelman and writer-editor Len Brown had adjacent offices that opened into Faye's area, as did my office, which was near the offices of the imaginative Art Spiegelman, designer Rick Varesi and gagwriter Stan Hart, who had married into the company and came in only one day a week. Hart wrote the Mad movie satires and later was a two-time Emmy-winner as a scripter for The Carol Burnett Show. A door on the other side of Gelman's room led to the office of the clever cartoonist and entertaining raconteur Larry Riley, whom I described in the third installment of this series about Topps. Sometimes Jay Lynch came to New York and worked periodically in the Product Development Dept.

Each day when I entered the building, as I recall, I went past a small sign that read, "Uneeda Doll Co." The floor of my office could get quite hot, and one day I peered into the ground floor area occupied by the Uneeda company and saw fumes rising from giant boiling vats. Later I began to wonder if seepage from those fumes is why we were all going wacky in Product Development.

One day in the summer of 1968, I told Woody I was going out, left the overheated office, exited the Bush Terminal and turned on 3rd Avenue toward Bay Ridge, perspiring as I walked through the broiling Brooklyn heat to a distant supermarket. At that time of day, the place was almost deserted. I wandered the aisles, sometimes just standing and reading the copy on containers to see what might be twisted into something goofy.

I looked up and noticed the store manager at the end of an aisle, staring at me. Since my actions were not those of a usual grocery shopper, he thought I was getting ready to steal something. After making my purchases, I headed back to Topps, carrying a paper bag filled with parody potentials, including a can of frozen orange juice concentrate.

I set these up near my drawing table, locked up and took the train back to Manhattan. When I opened the office door on Monday morning, there was a surprise. With the heat rising to a bake oven temperature during the weekend, the orange juice had exploded, leaving an orangey stickiness scattered over the drawing table and the wall. It was still stuck to the wall when I left New York and moved to Boston.

Google Street View screenshot at right shows where Topps was located at 254 36th Street in Brooklyn. At left is corner of 36th Street and 3rd Avenue where Woody Gelman and Len Brown would park their cars beneath the Gowanus Expressway.

Google Street View screenshot at right shows where Topps was located at 254 36th Street in Brooklyn. At left is corner of 36th Street and 3rd Avenue where Woody Gelman and Len Brown would park their cars beneath the Gowanus Expressway.Labels: gelman, larry riley, len brown, lynch, memoir, topps, wacky

Friday, April 09, 2010

Topps #8: Bonnie and Clyde fumetti

I designed the Krigstein-influenced pages above as a section in The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook, published by Personality Posters in 1968. The story behind the creation of this book might be just as interesting as the book itself. (For full enlargement of the images, click and when you go to the next page, click again with the crosshairs cursor.)

Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde was released in August 1967. I must have seen it that fall, and a few months later I read The True Story of Bonnie and Clyde as Told By Bonnie's Mother and Clyde's Sister (Signet, 1968), a reprint of Jan Fortune's Fugitives, The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker (1934). This book and the movie made me aware that Bonnie Parker had kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about the escapes of the Barrow gang from the law. It occurred to me that a facsimile of her scrapbook would make an interesting book, and I decided to present the idea to Woody Gelman, the publisher of Nostalgia Press.

In the spring of 1967, Art Spiegelman had introduced me to Woody Gelman at the historic Pete's Tavern, where O. Henry wrote "Gift of the Magi" in 1902. As a trial test, Gelman gave me an assignment to write and design an article on the Dionne Quintuplets for his planned Nostalgia Illustrated magazine. I found Gelman's clever concept, to do a magazine like a comic book, quite appealing and workable. (For instance, one article recreated a famous boxing match with a full page for each round.) After I wrote the Dionne article, I had to plow through a stack of Dionne paper dolls and other such memorabilia, calculating how to merge text and images into rows of panels.

Woody liked the finished result, so in the summer of 1967, I daily left Manhattan and rode the subway to the Bush Terminal in Brooklyn where Gelman was the art director of Topps Chewing Gum. I had office space at Topps, but I was working on Nostalgia Press projects. Almost immediately, he became nervous when he realized that Joel Shorin, the head of Topps, might be curious to know why non-Topps work was happening on the premises, so he would only meet with me during his lunch hour. By the end of the year, however, I was hired by Gelman to work full time in his department, drawing cartoon roughs and gags for Topps non-sports cards. (Click on the "topps" label at bottom to see the previous posts.)

By 1968, I was very familiar with Woody's publishing plans, and it seemed to me a book about the real Bonnie and Clyde could be a success for Nostalgia Press. I walked into Woody's office and outlined the book I wanted to create for him, The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook, a simulation of Bonnie Parker's actual scrapbook. I was quite surprised when he rejected the concept with very little discussion.

But the real surprise came a week later: He called me into his office and said, "Listen, my daughter Barbara has a great idea -- a book that will resemble Bonnie Parker's scrapbook. Here, I'm going to transfer her call to your phone."

If you think that sounds strange, imagine how I felt. I stood there, pole-axed. Had he simply forgotten our previous meeting? Perhaps I should have put the book's premise on paper instead of making a verbal presentation. Then I could have shown him a sheet of paper and waited for his reaction. To this day, I don't understand what happened there. But the nepotistic situation was a genuine trap. He was my boss, and I wanted to keep the job. So rather than fly into a rage, I said nothing and became a willing victim.

With the project underway, Woody mentioned a freelancer, Bill Hogarth, who he said was an expert at preparing presentations, and a week later, he showed me the dummy mock-up Hogarth had assembled. It showed a cover and a few opening pages. The rest of the presentation had blank pages.

Barbara Gelman took that presentation and went out to pitch the book. Despite the success of the movie, no one was interested. As I recall, she was rejected by nine publishers. However, at that time, Personality Posters was hot, and their posters were everywhere. From their main office at 74 Fifth Avenue, they also had a successful mail-order operation going with their only book, Who Was That? This was a picture book about familiar and unfamiliar character actors, and they sold it through full-page newspaper ads.

Because of the Bonnie and Clyde movie, posters of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were Personality Posters' biggest sellers. But time was a factor. They agreed to publish The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook if it could be delivered in one week. They planned to market it the same way they sold Who Was That?

Barbara brought in the writer Ron Lackmann. This struck me as odd because there was nothing really to write except a few captions. I believe that kick-started Lackmann's career, since he went on to do more than 30 books in the past 40 years. (What I didn't know at the time was that it was more nepotism. Lackmann died two months ago and from obituaries I learned that he and Barbara had been living together for the past 50 years.)

A stack of 1930s news photos was acquired by Barbara from the stock photo service, Black Star. I decided the book needed Bonnie and Clyde movie stills. I went to the Warner Bros. offices at 666 Fifth Avenue and met with the head publicist who listened with interest as I explained what we were doing. He went away and came back carrying a huge binder with all the photo prints grommeted together. He told me to write down numbers of the stills I wanted, and I gave him a list with 70 numbers. When I went back to Warner Bros., they handed me a manila envelope filled with prints of all the stills I had requested.

To meet the seven-day deadline, a team of Topps people worked on the book after five o'clock and during lunch hours. This included polished production art by cartoonist Rick Varesi, whose usual job was creating rough comps for Topps packaging and products, and type mark-up by a nice guy named Paul, who worked in the Topps production department.

I began designing the page layouts, working my way through the pile of Black Star pictures. Since numbers on the stills from Warner Bros. were shuffled randomly, there was no way to put them in the proper narrative sequence, and I visualized a filmic fumetti. In Italian, the word "fumetti," literally "little puffs of smoke," refers to all comics, since speech balloons resembled smoke. After WWII, photo comics became wildly popular in Italy, and Fellini's The White Sheik (1952) is an amusing comedy film about a performer (Alberto Sordi) in the Italian photo comics industry. In English, the term "fumetti" was adopted as a label for photo comics in Harvey Kurtzman's Help! and elsewhere after the word was popularized in a 1959 Time article.

Working from my memory of the movie, I shuffled stills into what I hoped was the correct order. I had a notion to use photos in a vein similar to the Futurist painters and the comic book stories of Bernard Krigstein, in which composition, size and dimension relate to the underlying emotions and add to the impact of the narrative. I did six pages of layouts to create a pantomime photo story that would show the whole movie like a comic strip. I compressed all the stills into those six pages, trying different arrangements as I recalled both the film's editing and past pages drawn by Krigstein. Soon I saw the cascading images almost automatically juggled into the proper places with a jigsaw precision. For the final shoot-out page, I repeated some stills large/small/smaller and tried a Krigstein-like staccato effect in the design. The finale of the movie was an extended sequence of quick-cut editing, and I attempted to duplicate that on the printed page.

At the end of the week, we had succeeded in assembling the entire book. On the phone, Barbara told me to put my name in the byline, but I had such a negative reaction to her intrusion into my book proposal that I refused. The book looked slick and unusual, and we had met the deadline.

Personality Posters ran a large newspaper ad in The New York Times just as they had done with Who Was That? As soon as the ad appeared, Black Star sued Personality Posters, claiming that the ad violated the contractual agreement for one-time only use of the old news photos. I can't remember if Woody was included in this legal action, but I think he got out of it somehow. At any rate, that was it. There were no more ads, and there was no distribution of the book. One day I was walking on Broadway near 46th Street, and I went into the Personality Posters store. Next to the cash register were two tiny piles of the only books published by Personality Posters. They looked completely out of place in the poster store. I never saw The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook in any bookstore. What became of all the copies that were printed? I don't know.

During the months this was happening, a strange bit of synchronicity surfaced when I met Michael J. Pollard (Oscar-nominated for Bonnie and Clyde) shortly after he moved into the building directly across from where I lived on West 12th Street.

What became of Nostalgia Illustrated? It was never published. Instead, Woody sold it off to Magazine Management. They hired Alan Le Mond to edit a magazine which was titled Nostalgia Illustrated but was quite conventional in its approach. It had nothing to do with Woody's remarkable design concept of making a magazine look like a comic book. Even so, I became a contributor and for a while had an article appearing in each monthly issue.

A few years later, I suggested to Woody that if he did a display of his books at the Boston Book Fair, I would man the booth. This went as planned, and he and his wife came to Boston for the weekend. The Nostalgia Press books attracted a good deal of attention. However, I recall watching as two matronly types were very offended by the cover of The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook. They wandered off, muttering that they were going to complain to someone.

In 1975, I was in a bookstore paging through a book, The World of Art Deco (1973) by Bevis Hillier, a catalog of a touring exhibition with the same title. And that's how I learned that a copy of The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook had been included in that exhibition.

You've read the story of Jesse James

of how he lived and died.

If you're still in need;

of something to read,

here's the story of Bonnie and Clyde.

Now Bonnie and Clyde are the Barrow gang

I'm sure you all have read.

how they rob and steal;

and those who squeal,

are usually found dying or dead.

There's lots of untruths to these write-ups;

they're not as ruthless as that.

their nature is raw;

they hate all the law,

the stool pidgeons, spotters and rats.

They call them cold-blooded killers

they say they are heartless and mean.

But I say this with pride

that I once knew Clyde,

when he was honest and upright and clean.

But the law fooled around;

kept taking him down,

and locking him up in a cell.

Till he said to me;

"I'll never be free,

so I'll meet a few of them in hell"

The road was so dimly lighted

there were no highway signs to guide.

But they made up their minds;

if all roads were blind,

they wouldn't give up till they died.

The road gets dimmer and dimmer

sometimes you can hardly see.

But it's fight man to man

and do all you can,

for they know they can never be free.

From heart-break some people have suffered

from weariness some people have died.

But take it all in all;

our troubles are small,

till we get like Bonnie and Clyde.

If a policeman is killed in Dallas

and they have no clue or guide.

If they can't find a fiend,

they just wipe their slate clean

and hang it on Bonnie and Clyde.

There's two crimes committed in America

not accredited to the Barrow mob.

They had no hand;

in the kidnap demand,

nor the Kansas City Depot job.

A newsboy once said to his buddy;

"I wish old Clyde would get jumped.

In these awful hard times;

we'd make a few dimes,

if five or six cops would get bumped"

The police haven't got the report yet

but Clyde called me up today.

He said,"Don't start any fights;

we aren't working nights,

we're joining the NRA."

From Irving to West Dallas viaduct

is known as the Great Divide.

Where the women are kin;

and the men are men,

and they won't "stool" on Bonnie and Clyde.

If they try to act like citizens

and rent them a nice little flat.

About the third night;

they're invited to fight,

by a sub-gun's rat-tat-tat.

They don't think they're too smart or desperate

they know that the law always wins.

They've been shot at before;

but they do not ignore,

that death is the wages of sin.

Some day they'll go down together

they'll bury them side by side.

To few it'll be grief,

to the law a relief

but it's death for Bonnie and Clyde.

--Bonnie Parker

First stanza of "The Story of Bonnie and Clyde" by Bonnie Parker

(in Clyde Barrow's handwriting)

(in Clyde Barrow's handwriting)

I designed the Krigstein-influenced pages above as a section in The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook, published by Personality Posters in 1968. The story behind the creation of this book might be just as interesting as the book itself. (For full enlargement of the images, click and when you go to the next page, click again with the crosshairs cursor.)

Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde was released in August 1967. I must have seen it that fall, and a few months later I read The True Story of Bonnie and Clyde as Told By Bonnie's Mother and Clyde's Sister (Signet, 1968), a reprint of Jan Fortune's Fugitives, The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker (1934). This book and the movie made me aware that Bonnie Parker had kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about the escapes of the Barrow gang from the law. It occurred to me that a facsimile of her scrapbook would make an interesting book, and I decided to present the idea to Woody Gelman, the publisher of Nostalgia Press.

In the spring of 1967, Art Spiegelman had introduced me to Woody Gelman at the historic Pete's Tavern, where O. Henry wrote "Gift of the Magi" in 1902. As a trial test, Gelman gave me an assignment to write and design an article on the Dionne Quintuplets for his planned Nostalgia Illustrated magazine. I found Gelman's clever concept, to do a magazine like a comic book, quite appealing and workable. (For instance, one article recreated a famous boxing match with a full page for each round.) After I wrote the Dionne article, I had to plow through a stack of Dionne paper dolls and other such memorabilia, calculating how to merge text and images into rows of panels.

Woody liked the finished result, so in the summer of 1967, I daily left Manhattan and rode the subway to the Bush Terminal in Brooklyn where Gelman was the art director of Topps Chewing Gum. I had office space at Topps, but I was working on Nostalgia Press projects. Almost immediately, he became nervous when he realized that Joel Shorin, the head of Topps, might be curious to know why non-Topps work was happening on the premises, so he would only meet with me during his lunch hour. By the end of the year, however, I was hired by Gelman to work full time in his department, drawing cartoon roughs and gags for Topps non-sports cards. (Click on the "topps" label at bottom to see the previous posts.)

By 1968, I was very familiar with Woody's publishing plans, and it seemed to me a book about the real Bonnie and Clyde could be a success for Nostalgia Press. I walked into Woody's office and outlined the book I wanted to create for him, The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook, a simulation of Bonnie Parker's actual scrapbook. I was quite surprised when he rejected the concept with very little discussion.

But the real surprise came a week later: He called me into his office and said, "Listen, my daughter Barbara has a great idea -- a book that will resemble Bonnie Parker's scrapbook. Here, I'm going to transfer her call to your phone."

If you think that sounds strange, imagine how I felt. I stood there, pole-axed. Had he simply forgotten our previous meeting? Perhaps I should have put the book's premise on paper instead of making a verbal presentation. Then I could have shown him a sheet of paper and waited for his reaction. To this day, I don't understand what happened there. But the nepotistic situation was a genuine trap. He was my boss, and I wanted to keep the job. So rather than fly into a rage, I said nothing and became a willing victim.

With the project underway, Woody mentioned a freelancer, Bill Hogarth, who he said was an expert at preparing presentations, and a week later, he showed me the dummy mock-up Hogarth had assembled. It showed a cover and a few opening pages. The rest of the presentation had blank pages.

Barbara Gelman took that presentation and went out to pitch the book. Despite the success of the movie, no one was interested. As I recall, she was rejected by nine publishers. However, at that time, Personality Posters was hot, and their posters were everywhere. From their main office at 74 Fifth Avenue, they also had a successful mail-order operation going with their only book, Who Was That? This was a picture book about familiar and unfamiliar character actors, and they sold it through full-page newspaper ads.

Because of the Bonnie and Clyde movie, posters of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were Personality Posters' biggest sellers. But time was a factor. They agreed to publish The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook if it could be delivered in one week. They planned to market it the same way they sold Who Was That?

Barbara brought in the writer Ron Lackmann. This struck me as odd because there was nothing really to write except a few captions. I believe that kick-started Lackmann's career, since he went on to do more than 30 books in the past 40 years. (What I didn't know at the time was that it was more nepotism. Lackmann died two months ago and from obituaries I learned that he and Barbara had been living together for the past 50 years.)

A stack of 1930s news photos was acquired by Barbara from the stock photo service, Black Star. I decided the book needed Bonnie and Clyde movie stills. I went to the Warner Bros. offices at 666 Fifth Avenue and met with the head publicist who listened with interest as I explained what we were doing. He went away and came back carrying a huge binder with all the photo prints grommeted together. He told me to write down numbers of the stills I wanted, and I gave him a list with 70 numbers. When I went back to Warner Bros., they handed me a manila envelope filled with prints of all the stills I had requested.

To meet the seven-day deadline, a team of Topps people worked on the book after five o'clock and during lunch hours. This included polished production art by cartoonist Rick Varesi, whose usual job was creating rough comps for Topps packaging and products, and type mark-up by a nice guy named Paul, who worked in the Topps production department.

I began designing the page layouts, working my way through the pile of Black Star pictures. Since numbers on the stills from Warner Bros. were shuffled randomly, there was no way to put them in the proper narrative sequence, and I visualized a filmic fumetti. In Italian, the word "fumetti," literally "little puffs of smoke," refers to all comics, since speech balloons resembled smoke. After WWII, photo comics became wildly popular in Italy, and Fellini's The White Sheik (1952) is an amusing comedy film about a performer (Alberto Sordi) in the Italian photo comics industry. In English, the term "fumetti" was adopted as a label for photo comics in Harvey Kurtzman's Help! and elsewhere after the word was popularized in a 1959 Time article.

Working from my memory of the movie, I shuffled stills into what I hoped was the correct order. I had a notion to use photos in a vein similar to the Futurist painters and the comic book stories of Bernard Krigstein, in which composition, size and dimension relate to the underlying emotions and add to the impact of the narrative. I did six pages of layouts to create a pantomime photo story that would show the whole movie like a comic strip. I compressed all the stills into those six pages, trying different arrangements as I recalled both the film's editing and past pages drawn by Krigstein. Soon I saw the cascading images almost automatically juggled into the proper places with a jigsaw precision. For the final shoot-out page, I repeated some stills large/small/smaller and tried a Krigstein-like staccato effect in the design. The finale of the movie was an extended sequence of quick-cut editing, and I attempted to duplicate that on the printed page.

At the end of the week, we had succeeded in assembling the entire book. On the phone, Barbara told me to put my name in the byline, but I had such a negative reaction to her intrusion into my book proposal that I refused. The book looked slick and unusual, and we had met the deadline.

Personality Posters ran a large newspaper ad in The New York Times just as they had done with Who Was That? As soon as the ad appeared, Black Star sued Personality Posters, claiming that the ad violated the contractual agreement for one-time only use of the old news photos. I can't remember if Woody was included in this legal action, but I think he got out of it somehow. At any rate, that was it. There were no more ads, and there was no distribution of the book. One day I was walking on Broadway near 46th Street, and I went into the Personality Posters store. Next to the cash register were two tiny piles of the only books published by Personality Posters. They looked completely out of place in the poster store. I never saw The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook in any bookstore. What became of all the copies that were printed? I don't know.

During the months this was happening, a strange bit of synchronicity surfaced when I met Michael J. Pollard (Oscar-nominated for Bonnie and Clyde) shortly after he moved into the building directly across from where I lived on West 12th Street.

What became of Nostalgia Illustrated? It was never published. Instead, Woody sold it off to Magazine Management. They hired Alan Le Mond to edit a magazine which was titled Nostalgia Illustrated but was quite conventional in its approach. It had nothing to do with Woody's remarkable design concept of making a magazine look like a comic book. Even so, I became a contributor and for a while had an article appearing in each monthly issue.

A few years later, I suggested to Woody that if he did a display of his books at the Boston Book Fair, I would man the booth. This went as planned, and he and his wife came to Boston for the weekend. The Nostalgia Press books attracted a good deal of attention. However, I recall watching as two matronly types were very offended by the cover of The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook. They wandered off, muttering that they were going to complain to someone.

In 1975, I was in a bookstore paging through a book, The World of Art Deco (1973) by Bevis Hillier, a catalog of a touring exhibition with the same title. And that's how I learned that a copy of The Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook had been included in that exhibition.

Final resting place of the beleaguered Bonnie and Clyde Scrapbook

You've read the story of Jesse James

of how he lived and died.

If you're still in need;

of something to read,

here's the story of Bonnie and Clyde.

Now Bonnie and Clyde are the Barrow gang

I'm sure you all have read.

how they rob and steal;

and those who squeal,

are usually found dying or dead.

There's lots of untruths to these write-ups;

they're not as ruthless as that.

their nature is raw;

they hate all the law,

the stool pidgeons, spotters and rats.

They call them cold-blooded killers

they say they are heartless and mean.

But I say this with pride

that I once knew Clyde,

when he was honest and upright and clean.

But the law fooled around;

kept taking him down,

and locking him up in a cell.

Till he said to me;

"I'll never be free,

so I'll meet a few of them in hell"

The road was so dimly lighted

there were no highway signs to guide.

But they made up their minds;

if all roads were blind,

they wouldn't give up till they died.

The road gets dimmer and dimmer

sometimes you can hardly see.

But it's fight man to man

and do all you can,

for they know they can never be free.

From heart-break some people have suffered

from weariness some people have died.

But take it all in all;

our troubles are small,

till we get like Bonnie and Clyde.

If a policeman is killed in Dallas

and they have no clue or guide.

If they can't find a fiend,

they just wipe their slate clean

and hang it on Bonnie and Clyde.

There's two crimes committed in America

not accredited to the Barrow mob.

They had no hand;

in the kidnap demand,

nor the Kansas City Depot job.

A newsboy once said to his buddy;

"I wish old Clyde would get jumped.

In these awful hard times;

we'd make a few dimes,

if five or six cops would get bumped"

The police haven't got the report yet

but Clyde called me up today.

He said,"Don't start any fights;

we aren't working nights,

we're joining the NRA."

From Irving to West Dallas viaduct

is known as the Great Divide.

Where the women are kin;

and the men are men,

and they won't "stool" on Bonnie and Clyde.

If they try to act like citizens

and rent them a nice little flat.

About the third night;

they're invited to fight,

by a sub-gun's rat-tat-tat.

They don't think they're too smart or desperate

they know that the law always wins.

They've been shot at before;

but they do not ignore,

that death is the wages of sin.

Some day they'll go down together

they'll bury them side by side.

To few it'll be grief,

to the law a relief

but it's death for Bonnie and Clyde.

--Bonnie Parker

Labels: beatty, bonnie and clyde, dunaway, fumetti, gelman, memoir, penn, pollard, topps, warner bros.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Topps #3: Pee-wee's Big Adventure

.

.

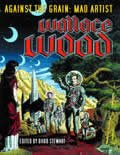

In 1966, at the request of Art Spiegelman, I submitted gags for Topps' Insult Postcard series. The first freelance gag I sold to Topps was part of that series: "Come alive! You're in the Monster Generation!" spoofed the familiar Pepsi Generation commercials. Wally Wood and Ralph Reese illustrated the series.

.

.In 1966, at the request of Art Spiegelman, I submitted gags for Topps' Insult Postcard series. The first freelance gag I sold to Topps was part of that series: "Come alive! You're in the Monster Generation!" spoofed the familiar Pepsi Generation commercials. Wally Wood and Ralph Reese illustrated the series.

Cover: Esau Andrews

Although Ralph took an extended leave from illustrating, he returns this month with a wild DC Comics tale, "The Thirteenth Hour," featuring monsters crawling over buildings a la Cloverfield. Look for it in issue #13 (May) of editor Angela Rufino's revival of House of Mystery for Vertigo.

Although Ralph took an extended leave from illustrating, he returns this month with a wild DC Comics tale, "The Thirteenth Hour," featuring monsters crawling over buildings a la Cloverfield. Look for it in issue #13 (May) of editor Angela Rufino's revival of House of Mystery for Vertigo.

As I explained previously, I began working with the Topps Product Development staff in December 1967. By then, Art had taken off for San Francisco, and when he returned a few months later, we would take sketchpads down the hall to the Topps cafeteria, which was deserted during the hours before and after lunch. While the kitchen staff prepared lunch, we would drink coffee and toss gags back and forth.

Others in the Product Development department, run by Woody Gelman, were the cartoonist-designer Rick Varesi, Len Brown (now a classic country DJ in Austin, Texas), Mad writer Stan Hart (who only came in once a week), the clever, creative Larry Riley and the secretary, Faye Fleischer. Riley was a terrific raconteur with hilarious tales of his years working on Paramount animated cartoons, and I regret never tape recording his stories. When he left Topps, he worked as an animator on Ralph Bakshi's movie, Fritz the Cat (1972).

Although Ralph took an extended leave from illustrating, he returns this month with a wild DC Comics tale, "The Thirteenth Hour," featuring monsters crawling over buildings a la Cloverfield. Look for it in issue #13 (May) of editor Angela Rufino's revival of House of Mystery for Vertigo.

Although Ralph took an extended leave from illustrating, he returns this month with a wild DC Comics tale, "The Thirteenth Hour," featuring monsters crawling over buildings a la Cloverfield. Look for it in issue #13 (May) of editor Angela Rufino's revival of House of Mystery for Vertigo.As I explained previously, I began working with the Topps Product Development staff in December 1967. By then, Art had taken off for San Francisco, and when he returned a few months later, we would take sketchpads down the hall to the Topps cafeteria, which was deserted during the hours before and after lunch. While the kitchen staff prepared lunch, we would drink coffee and toss gags back and forth.

Others in the Product Development department, run by Woody Gelman, were the cartoonist-designer Rick Varesi, Len Brown (now a classic country DJ in Austin, Texas), Mad writer Stan Hart (who only came in once a week), the clever, creative Larry Riley and the secretary, Faye Fleischer. Riley was a terrific raconteur with hilarious tales of his years working on Paramount animated cartoons, and I regret never tape recording his stories. When he left Topps, he worked as an animator on Ralph Bakshi's movie, Fritz the Cat (1972).

The inventive Larry Riley at Topps

Occasionally, other people would arrive and briefly take a crack at gagwriting. However, a special knack was required, and these wannabe humorists usually had odd and puzzling notions of what constituted humor.

One day Woody Gelman explained to us that the Topps execs were sending in a crackerjack humor writer to work on creating cards with us. I don't think Woody was too pleased about the situation of a newcomer crashing his party. Rick, Len, Larry and I were sitting in Woody's office waiting for the new guy to arrive. Expectations were high, because why was he being sent over unless he was a funny fellow? Indeed, he came in wearing a plaid jacket, a bowtie and big, confident grin. In retrospect, he looked sort of like Paul Reubens as Pee-wee Herman.

After a round of introductions and handshakes, Pee-wee took a seat, and Woody asked him to go right into his presentation. Pee-wee pitched a very strange concept. He said, "Okay, picture this. You show the world as it looks from a dog's point of view." Dead silence... as we all tried to comprehend just what he was describing.

I said, "So in other words, the dog is looking up, and there's a drawing of what he sees in an up-angle from ground level?"

"Yes," said Pee-wee with a big smile, obviously proud of this idea.

I continued, "So if that's the first card in a series of 44 cards, what would you do for the other 43 cards? Would card #2 be a cat looking up? Then maybe a hamster?"

He had no response. His smile faded. He began to twist slowly in the wind. And after that meeting, we never saw him again. In the bubble gum universe, another bubble had burst.

"Cowpoke in Africa" is another Krazy TV card with gag and color rough by me. John Severin drew the finish. The card caricatures Chuck Connors in the short-lived TV series Cowboy in Africa (1967-68). Coincidentally, Chuck Connors grew up in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, within walking distance of the Bush Terminal where Topps offices were located.

One day Woody Gelman explained to us that the Topps execs were sending in a crackerjack humor writer to work on creating cards with us. I don't think Woody was too pleased about the situation of a newcomer crashing his party. Rick, Len, Larry and I were sitting in Woody's office waiting for the new guy to arrive. Expectations were high, because why was he being sent over unless he was a funny fellow? Indeed, he came in wearing a plaid jacket, a bowtie and big, confident grin. In retrospect, he looked sort of like Paul Reubens as Pee-wee Herman.

After a round of introductions and handshakes, Pee-wee took a seat, and Woody asked him to go right into his presentation. Pee-wee pitched a very strange concept. He said, "Okay, picture this. You show the world as it looks from a dog's point of view." Dead silence... as we all tried to comprehend just what he was describing.

I said, "So in other words, the dog is looking up, and there's a drawing of what he sees in an up-angle from ground level?"

"Yes," said Pee-wee with a big smile, obviously proud of this idea.

I continued, "So if that's the first card in a series of 44 cards, what would you do for the other 43 cards? Would card #2 be a cat looking up? Then maybe a hamster?"

He had no response. His smile faded. He began to twist slowly in the wind. And after that meeting, we never saw him again. In the bubble gum universe, another bubble had burst.

"Cowpoke in Africa" is another Krazy TV card with gag and color rough by me. John Severin drew the finish. The card caricatures Chuck Connors in the short-lived TV series Cowboy in Africa (1967-68). Coincidentally, Chuck Connors grew up in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, within walking distance of the Bush Terminal where Topps offices were located.

Labels: gelman, krazy tv, memoir, monster, pee-wee, pepsi, ralph reese, reubens, topps, varesi